This has been quite a week for ancient DNA stories. First, the feature article in Archaeology magazine about the possibility of Neanderthal cloning. And yesterday, a research paper in Nature reporting the success of an international team in reconstructing the ancient genome of a 4000-year-old man from northwestern Greenland.

This has been quite a week for ancient DNA stories. First, the feature article in Archaeology magazine about the possibility of Neanderthal cloning. And yesterday, a research paper in Nature reporting the success of an international team in reconstructing the ancient genome of a 4000-year-old man from northwestern Greenland.

The latter project clearly takes us one step closer towards the ability to clone a Neanderthal, the subject of my last two posts. But today, I’d to focus on the new research from Greenland and what I think is important about it.

The team, led by Eske Willerslev, a very, very media-savvy researcher at the University of Copenhagen (whose work I have posted on before), obtained its ancient DNA from a tuft of human hair excavated by an archaeological team in 1986 from a site in northwestern Greenland. Willerslev and his colleagues make a strong claim that they have ruled out modern contamination.

The archaeologist who excavated the hair has gone on record stating in the 87 pages of supplementary material posted by Nature that none of the ethnic Greenlanders on his team touched the sample. He also affirms that no one who was likely of Asian descent handled the hair later during its storage in the museum.

So the team does indeed seem to be working with an uncontaminated ancient sample. And Willerslev–an expert on ancient DNA–and his Ph.D. student Morten Rasmussen report that the team has reconstructed 80 percent of the nuclear genome. Based on this, the team has learned a number of things.

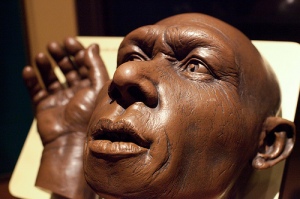

Number one, the hair belonged to a man who descended from northern-eastern Siberians who migrated to the New World as early as 6400 years ago. Number two, the individual in question had blood type A+, brown eyes, dark skin, a predisposition to baldness, a genetic adaptation to polar cold, and other identifiable traits.

Archaeologists already knew, however, from decades of painstaking study of artifacts that the early Greenlanders descended from northern Asian migrants. No surprises there. What is new, and I think very exciting, are all the details of appearance and physiology that have come to light about this particular individual– gleaned from just a few hairs.

Archaeology has never been very good at getting down to the level of the individual, particularly in that vast expanse of time we call prehistory. Excavations of house floors, middens, and shell mounds supply a lot of information on families, communities and populations. But they rarely say much if anything about individuals. And in places like North America, archaeologists try very hard now to avoid digging human remains–a major source of information about individuals–out of respect for Native American beliefs.

So this new ability to glean a lot of information about an individual from a human hair is bound to come in extremely handy, and I applaud the Danish team for their success. But its clear to me that such techniques are yet another worrying step along the road to cloning an ancient human or an ancient hominin.

The Danish led team is trying to calm our fears. “The genome we’ve reconstructed is no Frankstein’s monster,” team member Rasmussen told EurekAlert!. “It’s more like we’ve got the blueprints for a house, but we don’t know how to build it.”

For how long, I wonder. How long.

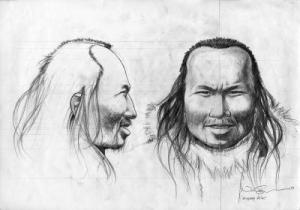

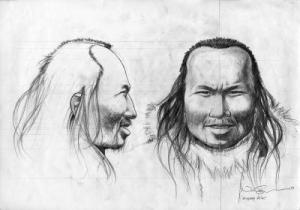

Reconstruction/drawing of Inuk by Nuka Godfredtsen.

Scientific American has just posted a very cool interactive feature online today that’s entitled “Twelve Events that Will Change Everything.” One of these game-changing events, suggests the magazine, will be human cloning.

Scientific American has just posted a very cool interactive feature online today that’s entitled “Twelve Events that Will Change Everything.” One of these game-changing events, suggests the magazine, will be human cloning.