When did land-loving humans first trust their fates to simple rafts and begin exploring the world by water? Most archaeologists would say some 50,000 years ago, when anatomically modern humans sailed from island southeast Asia to Australia. But Thomas Strasser, an archaeologist at Providence College in Rhode Island, dropped a bombshell last week at the annual meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America. Strasser reported that he had found several hundred double-edged cutting tools on the island of Crete that dated to at least 130,000 years ago. Some, said Strasser, looked very much like the hand-axes that Homo erectus wielded in Africa 800,000 years ago.

When did land-loving humans first trust their fates to simple rafts and begin exploring the world by water? Most archaeologists would say some 50,000 years ago, when anatomically modern humans sailed from island southeast Asia to Australia. But Thomas Strasser, an archaeologist at Providence College in Rhode Island, dropped a bombshell last week at the annual meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America. Strasser reported that he had found several hundred double-edged cutting tools on the island of Crete that dated to at least 130,000 years ago. Some, said Strasser, looked very much like the hand-axes that Homo erectus wielded in Africa 800,000 years ago.

Strasser now proposes that the ancient hominins voyaged out of Africa by primitive boat, island-hopping from Crete to Europe. “We’re just going to have to accept that, as soon as hominids left Africa, they were long distance seafarers and rapidly spread all over the place,” Strasser told Science News reporter, Bruce Bower.

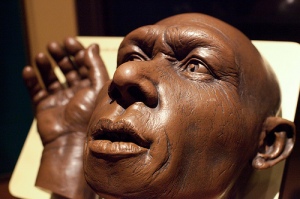

This new evidence sounds immensely intriguing, and I would certainly like to know much more. But I think that we are still a long way from seeing Homo erectus as a seafarer. Other evidence for such primeval ocean voyaging, after all, is very thin. Let me briefly recap. In 1998, a team led by Michael Morwood, an archaeologist at the University of New England in Armidale, Australia, excavated stone tools on the island of Flores in Indonesia (the same island that produced the so-called “Hobbit” remains of Homo floresiensis) that dated to some 800,000 years ago. This was the time period when H. erectus was roaming southeast Asia.

How did the ancient hominin get to Flores? Morwood himself suggested that they might have held on to logs as simple flotation devices, and kicked their across the narrow strait separating Komodo from Flores. But a more flamboyant researcher, Robert Bednarik, an independent scholar who heads The First Mariners project, proposes that H. erectus sailed there by raft. To demonstrate that such a voyage is indeed possible, Bednarik and several associates built a bamboo raft with paleolithic stone tools, and then sailed successfully on it from Lombok to the neighboring island of Sunbawa in a ten hour and twenty five minute crossing in rough seas.

So such a voyage is indeed possible in a simple raft. But most archaeologists working on the subject of coastal migration have been exceedingly reluctant to buy into the idea of seafaring H. erectus. When I interviewed half a dozen of the world’s leading experts on the subject two years ago while working on an article on ancient seafaring for Discover magazine, most suggested that that ancient hominins likely floated to Flores accidentally, after being blown out to sea in a storm.

A major sticking point for many is the cognitive ability of H. erectus. Many researchers believe that only modern humans possessed the necessary technological creativity to build a raft and the requisite intellectual ability to navigate at sea. But if Strasser’s new findings are accepted (and you can be sure that people will be looking very carefully at both the stone tools themselves and at the proposed dates), then it could be a whole new ballgame. I personally will be following this research with great interest.