Did our early human ancestors develop a written “code” some 30,000 years ago or more, inscribing and painting cave walls with its enigmatic symbols? This is the question posed by new research from Genevieve von Petzinger, a recently graduated master’s student at the University of Victoria in British Columbia, and the subject of a fascinating new article in New Scientist. What no one has mentioned so far, however, is that the idea of such an ancient script dates back to the nineteenth century and has a dark link to Nazi Germany.

Did our early human ancestors develop a written “code” some 30,000 years ago or more, inscribing and painting cave walls with its enigmatic symbols? This is the question posed by new research from Genevieve von Petzinger, a recently graduated master’s student at the University of Victoria in British Columbia, and the subject of a fascinating new article in New Scientist. What no one has mentioned so far, however, is that the idea of such an ancient script dates back to the nineteenth century and has a dark link to Nazi Germany.

First, however, let me summarize my understanding of von Petzinger’s very cool new research. Struck by the profusion of little circles, triangles, lines and other marks on rock-art-covered cave walls dating to Paleolithic times, von Petzinger created a massive database of all such recorded marks at 146 sites in France. (No one else had apparently been willing to undertake this seemingly thankless task, so full marks to von Petzinger.) The sites ranged in age from 35,000 to 10,000 years ago.

In analyzing this new database with her thesis advisor April Nowell, von Petzinger noticed that cave artists had repeated 26 different signs–including circles and triangles–over and over again. The artists had also used a kind of visual shorthand–inscribing just mammoth tusks instead of a whole mammoth, for example–which is common in pictographic languages. Moreover, in some caves, von Petzinger discovered pairs of signs, a type of grouping that characterizes early pictorial language.

This all sounds exceedingly interesting, though I am waiting to see the paper that the pair has just submitted to Antiquity. But I feel obliged to point out that the idea of a very early system of written symbols was strongly championed in Germany in the 1920s and 1930s by Herman Wirth, one of the most controversial prehistorians in Europe and the first president of the Nazi research institute founded by SS head Heinrich Himmler. (This institute was the subject of my last book, The Master Plan: Himmler’s Scholars and the Holocaust. In it, I wrote two full chapters on Wirth and his research. )

Wirth, who had a Ph.D in philology, was a man of great personal charm and many bizarre ideas. He became convinced that a blonde-haired, blue-eyed Nordic race had evolved in the Arctic, where it developed a sophisticated civilization complete with the world’s first writing system. Furthermore, he proposed that Plato’s description of Atlantis and its demise was in fact an accurate account of the catastrophe that befell the Nordic civilization on an Arctic island.

According to Wirth, the Nordic refugees from this disaster escaped to northern Europe, bringing with them their ancient writing system, an invention that later diffused to cultures around the world. So Wirth spent years poring over ancient European rock art, searching for evidence of this system and recording examples of circles, disks and wheels that he believed were ancient Nordic ideograms symbolizing the sun, the annual cycle of life, and so on.

I found Wirth’s ideas about an ancient master race and an Arctic Atlantis preposterous. Indeed, they would have been laughable had it not been for the fact that Himmler, the architect of the Final Solution, used Wirth’s published works to lend credence to the official Nazi line on the Aryan master race, and that Wirth, who died in 1981, still has many avid followers in Germany and Austria today. Indeed, I interviewed one of his ardent supporters.

I think that von Petzinger’s new research on Paleolithic symbols sounds immensely intriguing. It certainly fits with our growing awareness of the abilities of our human ancestors. Moreover, I want to state clearly that the Canadian researcher did not for a moment come under the influence of Herman Wirth and his ideas. Indeed, she proposes that the ancient sign language may have originated in Africa and arrived in Europe with modern humans–a proposal that would have horrified Wirth.

Nevertheless, I think it’s important to point out the troubled history of the idea of an ancient European script recorded in rock art. We cannot afford to forget in any way the Nazi past.

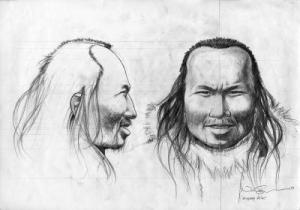

Today’s photo shows a plaster cast that Wirth made in the late 1930s of Bronze-Age rock art in Sweden. I photographed this cast in 2002 as it hung in a museum in a small Austrian town, Spital am Pyhrn. At the time, Wirth’s casts were clandestine Nazi memorials.