As regular readers will know, I recently fumed here over the poor conservation of a petroglyph-covered boulder at the Vancouver Museum, after reading a troubling post over at Northwest Coast Archaeology. I questioned the wisdom of removing such boulders and slabs from the places where they were created and installing them in museums. I then suggested that the Vancouver Museum repatriate the damaged boulder in question.

Since then, Northwest Coast has posted more on this disturbing state of affairs, and recently I received a great email on these issues from George Nicholas, an archaeologist at Simon Fraser University and the director of Intellectual Property issues in Cultural Heritage. George is kindly guest-blogging on this today. -HP

Since then, Northwest Coast has posted more on this disturbing state of affairs, and recently I received a great email on these issues from George Nicholas, an archaeologist at Simon Fraser University and the director of Intellectual Property issues in Cultural Heritage. George is kindly guest-blogging on this today. -HP

I think the notion that rock art is about more than the images is something that has been largely ignored, certainly by the public, but also by many archaeologists and anthropologists. People often tend to focus on the details of the images, rather than on the context of the rock art. But one doesn’t work without the other.

In his book Ways of Seeing, John Berger notes that before photography, before the age of reproductive technology, one could only see a particular image (such as the Last Supper fresco) in the church in which it was painted. The same obviously holds true for Lascaux and all other rock art.

Taken out of their geographic context, the images are divorced not only from the place itself (which may be imbued with meaning of its own), but also from the emotional landscape and viewscape. I’m sure you’ve been to petroglyph sites where there’s sort of a mystical feel to the place. I find that at the Three Sister’s Rockshelter in British Columbia’s Marble Canyon. The silence of the moss-filled forest that surrounds the blue-grey rock face adds an important dimension to the rock art.

And of course, we approach rock art from the perspective of the western world. Our worldview is based on a set of dichotomies: the distinctions between the natural and supernatural realms; between people and nature; between past, present, and future; between genders, and all the rest. Such distinctions may be absent, however, in many indigenous societies; they may live in a world in which ancestral spirits are part of this existence (owing to lack of separation between past and present; between natural and supernatural realms).

So all of this, then, begs several questions. What does rock “art” really represent? How are we supposed to view it? What should we do with it, from a heritage preservation perspective? Indeed, is rock art something that should be preserved?

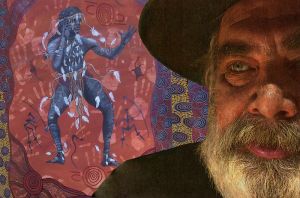

Most western archaeologists would say yes to the latter question. But in Australia, contemporary Aboriginal persons sometimes paint over ancient images as a way of continually replenishing the world; it is the act of painting that is important (like the creation of Navajo sand paintings used in healing ceremonies, and later destroyed, much to the consternation of western observers).

Most western archaeologists would say yes to the latter question. But in Australia, contemporary Aboriginal persons sometimes paint over ancient images as a way of continually replenishing the world; it is the act of painting that is important (like the creation of Navajo sand paintings used in healing ceremonies, and later destroyed, much to the consternation of western observers).

The Zuni people have a similar tradition. They carve wooden figurines of their war gods, the Ayahu:ta, and place them in outdoor shrines. After a period of time, the figurines are replaced with new ones. Zuni tribal member and archaeologist Edmund Ladd notes in his writings that “When a new image of the Ahayu:ta is installed in a shrine, the ‘old’ one is removed to ‘the pile,’ which is where all the previous gods have been lain. This act of removal specifically does NOT have the same connotations as ‘throwing away’ or ‘discarding.’ The image of the god that has been replaced must remain at the site to which it was removed and be allowed to disintegrate there.” So, from a Zuni perspective, proper stewardship is letting the ahayu:ta decay.

Rock art raises many fundamental issues, as well as conflicting claims that certain items of heritage belong to a specific group or are part of the heritage of human kind. In recent decades, archaeologists have been very much part of this debate.

My own position is that I see merit in both positions, but also that the tension between the two positions is important because it forces us (as archaeologists, as heritage managers, as member of descendant communities, etc) to think about the nature of heritage in new ways.

-George Nicholas

Above: The rock art of Bohuslan, Sweden. Photo by Julius Agrippa. Below: Contemporary Aboriginal artist Mundara Koorang. Photo by Novyaradnum.

Something about the strange strands didn’t fit. Patricia Sutherland spotted it right away: the weird fuzziness of them, so soft to the touch.

Something about the strange strands didn’t fit. Patricia Sutherland spotted it right away: the weird fuzziness of them, so soft to the touch.